Yes, around the year 142 AD, following the death of Bishop Hyginus, the Church of Rome stood at a defining crossroads. Marcion of Sinope, bishop of Sinope and a devout disciple of both the Apostle Paul and John, sought to become bishop of Rome not as an innovator, but as a restorer—determined to return the Church to its authentic Pauline foundation. According to Marcionite tradition, the first legitimate bishop of Rome was Linus, ordained by Paul, and succeeded by Anacletus, the second Pauline bishop. The Catholic faction, however, traced its authority through Peter, and claimed Clement—the first Petrine bishop of Rome—as the founder of their episcopal succession. After Anacletus’s death, the Pauline line weakened, and the Petrine succession gained exclusive control, establishing a single episcopal line that would come to dominate the Roman Church. This shift set a precedent of two competing apostolic jurisdictions—Pauline and Petrine—vying for the soul of the Church.

To support his effort, Marcion donated 200,000 sesterces to the Roman Church. His gospel message was radical and clear: the God revealed by Jesus Christ was a God of perfect mercy and goodness, wholly distinct from the false god Yahweh of the Hebrew scriptures—a god of wrath, judgment, and legalism. Alongside him, Valentinus of Egypt also sought influence, promoting a mystical Gnostic worldview. Yet both men were ultimately rejected in favor of Pius (later Pius I), who upheld the Catholic project of merging Jewish scripture with Christian revelation.

Marcion initially remained within the Roman community, leading a growing reformist faction. But on the Ides of July, 144 AD, Bishop Pius excommunicated him, returned his donation, and expelled him from communion. According to Marcionite tradition, the following day Marcion stood before the Roman clergy and solemnly declared:

“I will divide your Church and cause within her a division, which will last forever.”

Two years earlier, in 142 AD, Marcion had already been appointed bishop of Antioch, succeeding Cornelius, a Petrine-aligned bishop. Upon assuming the post, he resigned his episcopacy in his native Sinope, where he had previously led a small but faithful Pauline community. From Antioch—a city that at the time rivaled Rome in power and prestige—Marcion began organizing a new ecclesiastical order, founded entirely on the gospel of Paul, the Apostolicon, and the Evangelicon. Anatolia, his homeland, quickly became the heartland of Marcionism, where his message of freedom from the law and rejection of Yahweh found a devoted and expanding audience. Many eastern bishops were in closer communion with Antioch than with Rome, aligning themselves with Marcion’s gospel of grace.

Like Rome, Antioch had a history of dual apostolic lineage. According to Marcionite understanding, its first Pauline bishop was Ignatius, a disciple of Paul who upheld the primacy of grace. In contrast, Catholic tradition traced its Petrine succession in Antioch back to Evodius, regarded as the first Petrine bishop of Antioch, allegedly appointed by Peter himself. This legacy of duality set the stage for the schism that followed.

In response to Marcion’s rising influence and consolidation of the Pauline faction, the Catholic Church swiftly installed Heron II as a parallel Petrine bishop in Antioch shortly after Marcion’s excommunication in 144 AD. Heron II represented the institutional wing of the Church, rooted in apostolic succession through Peter and theological allegiance to the Hebrew scriptures. Antioch became a divided episcopate, with Marcion and Heron II embodying two rival theological visions—one grounded in law and prophetic continuity, the other in grace and the radical freedom of Christ revealed apart from the law.

It was also in Antioch, around 169 AD, that the Catholic bishop Theophilus began to edit the Evangelicon, reworking Marcion’s gospel to align with the Catholic view of scripture and doctrine. This redacted and shortened version would later circulate as the Gospel of Luke, stripped of its original anti-Judaic and Pauline clarity. It marked the beginning of Rome’s efforts to co-opt and neutralize Marcion’s scriptural legacy.

Following his excommunication, Marcion formally established a separate Church, declared himself Archbishop—a title later twisted by his Catholic opponents who mocked him as the “Archheretic”—and appointed trusted disciples to key episcopal seats across the Christian world. Among the most significant were:

Apelles, appointed bishop of Alexandria, who would later succeed Marcion as Archbishop after his martyrdom.

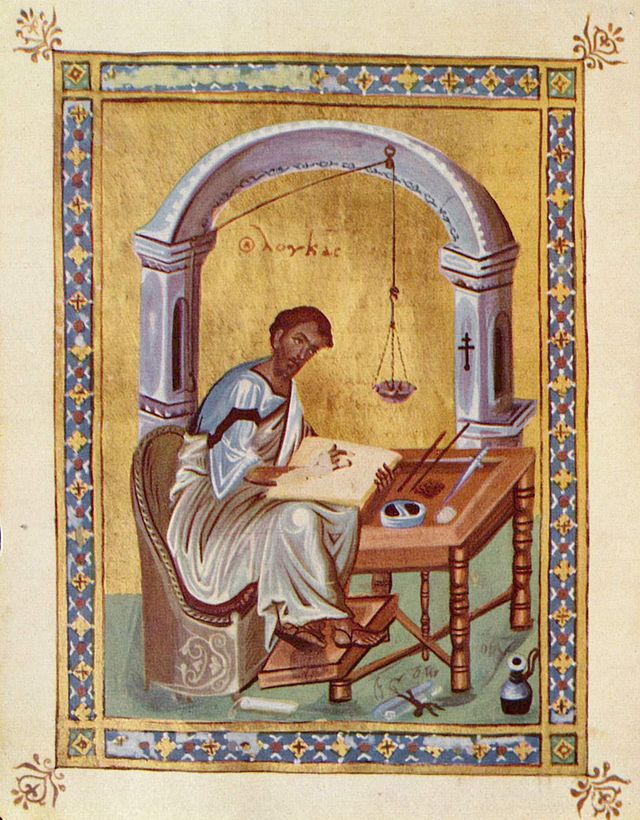

Lucanus, appointed as the Marcionite bishop of Rome, continuing the Pauline witness in the heart of Catholic power.

Onesimus, appointed bishop of Ephesus, a church founded by Paul and long faithful to its Pauline heritage. It was in Ephesus that Marcion had originally served as a disciple of the Apostle John.

Damas, made bishop of Magnesia on the Maeander, a city eager to embrace Marcion’s gospel over Rome’s legalism.

Polybius, installed as bishop of Tralles, an Anatolian city that openly rejected Petrine ecclesiology.

Metrodorus, named bishop of Smyrna, where he led the Marcionite community in open and ongoing rivalry with the Petrine faction headed by Polycarp, one of Marcion’s most relentless adversaries. It was in Smyrna that Marcion had earlier delivered his famed Homily to Diognetus.

These churches—Alexandria, Rome, Ephesus, Magnesia, Tralles, Philadelphia, and Smyrna—stood at the forefront of Marcion’s ecclesiastical rebellion. Each declared its loyalty to the God revealed by Christ alone, rejected the authority of the Hebrew scriptures, and severed communion with the Roman and Petrine hierarchy. In these cities of Anatolia, the gospel of Paul took deep root, as Marcionite bishops took their place beside, or in place of, their Catholic counterparts.

In 154 AD, Marcion returned to Rome, not to debate, but to face martyrdom. He had been condemned by Roman authorities for fomenting division among the Christian communities of the capital. During this final journey, he encountered his lifelong adversary, Polycarp of Smyrna, who, upon seeing him, famously declared:

“Yea, I know thee as the first-born of Satan.”

Unmoved by scorn or condemnation, Marcion was led into the Colosseum, where he was martyred for the gospel he believed had been revealed through Paul alone—a gospel of grace, liberty, and the worship of the true God, wholly distinct from the false deity of the law.

Though the Catholic Church would enshrine figures like Pius and Polycarp as saints and defenders of orthodoxy, it was Marcion’s legacy that forced the early Church to define its canon, its creeds, and its institutional authority. The division he foretold became real—and in many ways, has never been healed.