Moreover, the direction of textual change supports Marcionite Priority. Catholic redaction concentrated on the Pauline epistles, where concise letters were expanded and interpolated to align with emerging doctrine. By contrast, in the Evangelicon, editors altered wording, removed passages, and redistributed verses to manufacture the fourfold Gospel. The structure and content of Marcion’s texts suggest not a Catholic abridgment, but rather earlier, more primitive versions that were subsequently reshaped to conform to Catholic orthodoxy.

Marcionite Church of Christ

Birthplace of the first Christian Holy Bible.

Home of the oldest inscription bearing the name of Jesus.

Originators of the earliest Christian hymnbook.

Creators of the original Christian apologia.

One Testament.

The Marcionite Church was once the largest Christian body in the world, encompassing millions of adherents across the known regions of antiquity. In 128 C.E., it produced the first Christian Bible, known as the Testamentum. This sacred text contains the Gospel of the Lord Jesus Christ, as revealed to the Apostle Paul, along with the original ten Epistles attributed to him. The Testamentum stands as the foundational canon of Christian scripture, from which nearly all later denominations ultimately derive their origins.

Marcionite Christians firmly rejected the Hebrew Bible and the god depicted within it, recognizing a fundamental incompatibility between its teachings and the message of salvation brought by Jesus Christ. This theological distinction—clear and demonstrable through the scriptures themselves—is precisely why the Hebrew Bible was excluded from the original Christian canon.

One

Gospel

Ten

Epistles

"I do not frustrate the grace of God: for if righteousness come by the law, then Christ is dead in vain."

Galatians 2:21

MARCIONITE CHURCH OF CHRIST

Prima Scriptura.

Marcionite Christians are not Gnostics. Our faith is not built on hidden teachings or secret revelations. Instead, it is grounded in Prima Scriptura—the authority of the first Christian Bible, the Testamentum—which openly and unapologetically proclaims the truths of our doctrine. These beliefs not only stand in the light of public scripture but also predate the formation of any other existing Christian church.

Though once vast in size and global in reach, the Marcionite Church has never been a burdensome institution encumbered by rigid hierarchies or layers of ecclesiastical control. Every individual is a sovereign child of God, fully capable of communion with Him in the present moment. The purpose of the Marcionite Church is to foster and strengthen that divine relationship, while offering a spiritual community grounded in fellowship, encouragement, and shared faith.

Prima Sciptura

Sola Fide

Credobaptism

Trinitarian

"I marvel that ye are so soon removed from him that called you into the grace of Christ unto another gospel: Which is not another according to my gospel; but there be some that trouble you, and would pervert to a gospel different from that of Christ."

Galatians 1:6-7

MARCIONITE CHURCH OF CHRIST

Pre-Nicene Christianity.

In the years following the resurrection of Christ, the early Christian community was marked not by unity and peace, but by intense division and theological strife—even among the Apostles themselves. Far from being a harmonious beginning, this era was one of doctrinal conflict and spiritual contention.

At that time, the teachings and accounts of Jesus Christ were transmitted primarily through oral tradition, with written scriptures being rare, fragmented, and difficult to access. Competing narratives—many of them spurious or falsified—began to circulate widely, contributing to confusion and discord among believers.

It was amid this backdrop of controversy that Marcion of Sinope—a shipbuilder and bishop—undertook the monumental task of gathering and preserving the authentic writings of the Apostle Paul, along with the true Gospel of the Lord Jesus Christ as it had been received. These sacred texts, previously entrusted to the Apostle John, were compiled and formally transcribed by Marcion in 128 C.E., forming the first Christian Bible: the Testamentum. Notably, this compilation excluded the Hebrew Bible, reflecting the theological clarity and distinction upheld by Marcionite doctrine.

Using the Testamentum as the foundation, Marcion established the Marcionite Church, which quickly expanded throughout the known world. Even the early Catholic Church relied on the Testamentum as a reference for translating Christian scriptures from Greek into Latin—though subsequent revisions and interpolations significantly altered the original message.

Today, a growing number of biblical scholars and theologians recognize that the canonical gospels found in modern Bibles are heavily edited versions of an earlier, purer gospel—the original Gospel of the Lord Jesus Christ preserved in the Testamentum.

"And no man putteth new wine into old bottles; else the new wine will burst the bottles, and be spilled, and the bottles shall perish."

Evangelicon 2:36

MARCIONITE CHURCH OF CHRIST

Council of Nicaea.

Centuries after the Testamentum was first transcribed in 128 C.E., the Hebrew Bible and various writings of uncertain origin were forcibly appended to it by imperial decree. This act was carried out under the authority of a pagan Roman emperor’s political-religious council, not by divine inspiration or apostolic mandate.

The Council of Nicaea, convened in 325 C.E., initiated this distortion. Its decisions amounted to a theological defacement—comparable to desecrating a sacred text with ideological graffiti. These alterations were later ratified and codified by the Council of Rome in 382 C.E., further obscuring the original message of the Gospel.

In contrast, the earliest Christians, as recorded in the Apostolic Council of Jerusalem in 48 C.E., affirmed that the true revelation of God came through Jesus Christ—not through the Hebrew Bible. That text reflects the customs, laws, and tribal deity of a people and religion wholly distinct from the universal salvation proclaimed in the Testamentum. It is alien to the spirit, doctrine, and purpose of authentic Christianity.

"But I certify you, brethren, that the gospel which was preached of me is not after man. For I neither received it of man, neither was I taught it, but by the revelation of Jesus Christ."

Galatians 1:11-12

MARCIONITE CHURCH OF CHRIST

Ready to reclaim your Christian faith?

There is profound comfort in rediscovering the true origins of your Christian faith and holding in your hands the first Christian Bible—the Testamentum. With a deeper understanding of the Church’s authentic history and teachings, you are now called to move forward, remaining actively connected with fellow believers in the Marcionite Christian community.

“We are the price of the blood of Jesus.”

— Marcion of Sinope

Questions

Any serious discussion of the Marcionite Christians must begin with the recognition that, aside from their unwavering belief in the Testamentum—a text embraced by many of the earliest followers of Christ, not solely by Marcionites—the precise contours of their doctrine remain only partially known.

Marcion of Sinope’s foundational work, the Antitheses, presented a systematic argument demonstrating that the god portrayed in the Hebrew Bible is fundamentally distinct from the true God revealed by Jesus Christ. Tragically, this text—along with many others—was systematically suppressed and destroyed by Marcion’s opponents. Ironically, it is from these very adversaries that much of our surviving knowledge of his teachings must now be reconstructed.

With that context in mind, let us turn to address some of the most frequently asked questions and common misconceptions surrounding the Marcionite Church.

Historical Questions

Who was Marcion of Sinope?

Marcion of Sinope was a bishop and affluent shipowner from the chief port city of Sinope in Pontus, located on the southern coast of the Black Sea. He was the son of Bishop Philologus of Sinope, traditionally identified as one of the Seventy Disciples. Born around 70 C.E., Marcion began his ministry in Anatolia circa 98 C.E. as a disciple of the Apostle John. His work was already known and commented upon by Polycarp by 115 C.E. Marcion died a martyr in the Colosseum near the end of 154 C.E., having lived approximately 85 years.

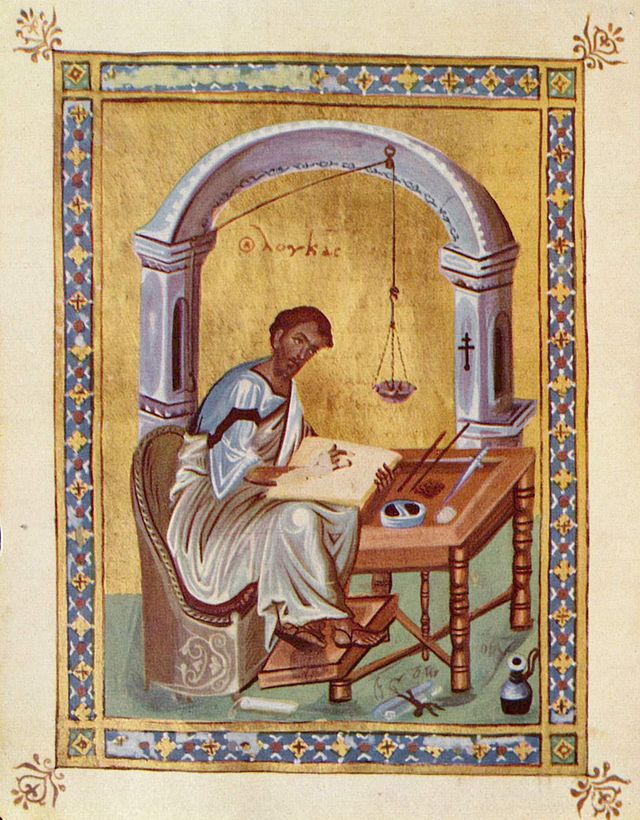

Marcion’s legacy is monumental in the history of Christianity. He authored the first work of Christian apologetics, compiled the earliest Christian hymnbook, and produced the first Latin translations of Christian scripture. His most enduring and transformative achievement, however, was the compilation of the first Christian Bible—the Testamentum. This canon included the Gospel of the Lord Jesus Christ, as revealed to the Apostle Paul, and the original ten Pauline epistles.

To assemble this sacred text, Marcion and his fleet retraced the missionary journeys of the Apostle Paul across the Roman Empire. He visited the Pre-Nicene churches established by Paul, gathering and preserving the apostle’s original Greek writings and letters. For the first time in Christian history, these documents were transcribed and bound in a codex—a book format—making the Gospel and epistles widely accessible to the faithful.

In the course of compiling these scriptures, Marcion discerned a stark theological divide. He compared the God revealed through Jesus Christ with the violent, retributive deity portrayed in the Hebrew Bible. His conclusion was decisive: they were not the same God. To articulate this revelation, he authored Antithesis, a seminal text in which he set forth his arguments and scriptural comparisons. This work sparked a profound schism among early Christian leaders, with each faction branding the other as heretical.

Around the late 130s C.E., Marcion traveled to Rome and joined the Roman Christian community, offering a significant donation of 200,000 sesterces to the church. However, theological disputes quickly emerged. On July 15, 144 C.E., he was formally denounced as a heretic and excommunicated by the Church of Rome, which returned his donation.

His influence endured long after his death, laying the foundation for a church that once spanned the known world and shaped the earliest formation of Christian scripture.

Who were the Marcionite Christians?

The Marcionite Christians are among the earliest and most influential communities in the history of Christianity. They are credited with numerous foundational contributions to the faith, including the compilation of the first Christian Bible (Testamentum), the creation of the earliest Christian hymnbook, and the composition of the first work of Christian apologetics. Remarkably, the oldest known inscription bearing the name of Jesus was discovered carved into the entrance of a Marcionite church in Syria.

This church was erected by Paul of Lebaba, a Marcionite presbyter, in the village of Lebaba on October 1st, 318 C.E. The inscription, written in reference to Jesus Christ, reads as follows:

“The meeting-house of the Marcionites, in the village of Lebaba, of the Lord and Saviour Jesus the Good – Erected by the forethought of Paul a presbyter, in the year 630 [Seleucid era].”

Discovered by French archaeologists in 1870, this inscription stands as the oldest surviving reference to Jesus Christ in a Christian context carved in stone.

The Marcionite Church rapidly became one of the largest and most widespread Christian movements of the early centuries, maintaining a strong presence across the Roman Empire and beyond. However, during the fourth century, as the Catholic Church gained imperial favor, Marcionite Christians—along with other non-Catholic sects—were subjected to systematic persecution. Roman emperors, now aligned with Catholic orthodoxy, sought to extinguish all divergent forms of Christianity, including Marcionism.

Despite the growing hostility within the Empire, Marcionite Christianity endured well beyond Rome’s borders. It continued to thrive in regions such as Syria and northeastern Persia into the tenth century, preserving its distinctive doctrines and practices.

Central to Marcionite belief was the conviction that the Apostle Paul alone had received and transmitted the full and true message of Jesus Christ. Only Paul’s writings were considered authoritative scripture. Marcion’s theological focus was deeply rooted in the Pauline tradition, which he saw as radically distinct from—and indeed incompatible with—the teachings of the Hebrew Bible.

Marcion regarded all efforts to reconcile the Gospel of Jesus Christ with the law-bound, wrathful deity of the Hebrew scriptures as a fundamental distortion of Christian truth. For him, Paul’s contrast between law and grace, wrath and mercy, works and faith, flesh and spirit, sin and righteousness, death and life, represented the essence of divine revelation. In this, he saw the pure expression of the Gospel—a message of deliverance, not bondage; of spirit, not flesh; of grace, not judgment.

What was the reaction to Marcionite Christians?

Following Marcion’s evangelistic mission across the Roman Empire in the second century, several energetic responses emerged—many of which can be seen as indirect reactions to his foundational work. Among these were the expansion of the New Testament canon, the development of Apostolic Tradition, the formulation of the Rule of Faith, and the doctrine of Apostolic Succession. Each of these innovations served to counter Marcion’s uncompromising commitment to Prima Scriptura—the principle that scripture alone, not tradition or hierarchy, is the foundation of Christian belief.

The doctrine of Apostolic Succession enabled emerging Catholic authorities to claim divine legitimacy in determining which texts were to be regarded as “authentic” and which were “spurious.” This conferred on Church leadership the power to enforce doctrinal conformity, often by retroactively assigning apostolic origin to texts that aligned with their theological agenda. As a result, a flood of gospels, interpolated epistles, and forged writings began to circulate—many bearing false claims of apostolic authorship. Criteria for canonization were arbitrarily established: a text had to claim apostolic origin, or at least connection to an apostle, and it had to reflect beliefs already widespread within the Catholic faction. This framework, known as “Apostolic Tradition,” effectively institutionalized the attribution of Catholic customs and doctrines to the Apostles—regardless of historical authenticity.

Because many of these writings lacked legitimate claims to apostolic origin, elaborate legends and theological rationales were constructed to justify their inclusion in the canon. This is a particularly sobering realization for modern Protestants who adhere to Sola Scriptura, often unaware that several New Testament books owe their canonical status solely to assertions of tradition rather than demonstrable apostolic authorship. As Pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer aptly observed, “Protestants, in denying the authority of tradition, have cut off the branch on which they sit.”

Marcion’s missionary advance also triggered a flood of apologetic and polemical writing. Pseudepigraphal texts expanded in the second century with explicit anti-Marcionite polemics, such as the forged Third Epistle to the Corinthians, and even the Apostles’ Creed itself was crafted or edited to counter Marcionite theology. Scholars such as Arthur C. McGiffert view the creed precisely as a reaction meant to counter Marcion’s radical theology.

The renowned scholar Adolf von Harnack went so far as to describe Marcion as the “father of the Catholic Church”—not because Marcion founded it, but because the Catholic Church largely defined itself in opposition to his teachings. The Roman Church’s reaction to the rapid spread of Marcionite congregations across the Empire during the early second century compelled it to construct a more centralized hierarchy and formalize its canon, doctrine, and institutional presence.

Marcion’s introduction of a clearly defined and limited scriptural canon presented a direct challenge to the developing Catholic tradition. His Testamentum, containing only the Gospel of the Lord and the ten original Pauline epistles, forced the Catholic Church to confront a difficult question: if Marcion’s canon was not the true one, then what was? In response, the Church began the long and contested process of expanding the New Testament—a process rooted not in original apostolic witness, but in theological reaction to Marcion’s radical clarity.

What is the Marcionite priority?

Much of what is known about Marcion and his theological work comes to us through the writings of his detractors. Notably, every major critique of Marcion’s teachings was written posthumously—after his death, when he could no longer defend himself or refute the accusations leveled against him. Among his most vocal opponents was the early Catholic Church Father Tertullian, who alleged that Marcion had “mutilated” the Gospel of Luke, selectively removing passages that did not align with his beliefs. However, modern scholarship increasingly supports the theory of Marcionite Priority—the view that Marcion’s Evangelicon is the earlier text, and that what we now know as the Gospel of Luke is a later, expanded version edited to reflect emerging Catholic theology.

Some scholars suggest that this editorial transformation was undertaken by Theophilus, bishop of Antioch, around 169 C.E. According to this view, Theophilus substantially expanded the original Evangelicon, adding material he deemed necessary for a complete Gospel account, and retroactively named the result the Gospel of Luke.

Crucially, there is no surviving documentary evidence of a pre-Marcionite Gospel of Luke or pre-Marcionite Pauline Epistles. This strongly suggests that Marcion’s canon was in use in Rome before 144 C.E., and that the manuscripts he employed predate the oldest known Pauline manuscripts, such as the Egyptian papyri dating to around 200 C.E. Thus, the Pauline texts in Marcion’s Testamentum are likely closer to the original apostolic writings than the later, edited versions adopted by the Catholic Church.

Pauline versus Petrine?

Controversy took root in Christianity from its earliest days. When the Apostle Paul converted, he did not seek to reform Judaism but to leave it behind entirely. Paul believed that he was led by the indwelling Spirit of Christ and that his gospel was not of human origin, but received through divine revelation from the risen Jesus. For Paul, Christ was the universal Savior of all humanity—Jew and Gentile alike.

Throughout the first and second centuries, a profound theological divide emerged between the followers of Paul and those aligned with the Apostle Peter. Pauline Christians held that the Gospel was a new, universal covenant—open to all, independent of Jewish law. In contrast, Petrine Christians insisted that Christianity was an extension of Judaism, requiring adherence to Jewish customs such as circumcision. In their eyes, uncircumcised converts were illegitimate Christians, and bishops who had not come from the Jewish priesthood were not valid clergy. Some extreme groups, such as the Ebionites, took this position even further, demanding strict adherence to Mosaic law and denying the legitimacy of Paul’s apostleship altogether.

This division manifested in ecclesiastical conflicts as well. Catholic canon law, said to be derived from apostolic tradition, later insisted that there could be only one bishop per city. Yet in Antioch—one of the earliest Christian centers—records show the simultaneous presence of two bishops: Evodius, ordained by Peter, and Ignatius, ordained by Paul. This dual succession reflects the deeper theological and institutional schism between the Pauline and Petrine streams of early Christianity.

A similar tension appears in the early episcopate of Rome. Ancient sources suggest that Linus, recognized as the first bishop of Rome, was ordained by Paul. He was followed by Anacletus (or Cletus), also said to have been appointed by Paul. Clement, traditionally regarded as ordained by Peter, is listed as third or even fourth in some episcopal lists. However, in other traditions—especially those emphasizing Petrine primacy—Clement is portrayed as the first legitimate bishop, as if the Roman church only attained apostolic legitimacy once a successor of Peter took office. Jerome himself remarked on this ambiguity, writing: “Clement… the fourth bishop of Rome after Peter, if indeed the second was Linus and the third Anacletus, although most of the Latins think that Clement was second after the apostle [Peter].”

This complex and overlapping episcopal lineage strongly suggests that, as in Antioch, Rome too had parallel jurisdictions—one tracing its authority to Paul, the other to Peter. This dual succession helps explain the difficulty historians face in establishing clear dates and order for the earliest bishops of Rome. Rather than a single, unified episcopacy, early Christianity appears to have operated under competing apostolic lineages, shaped by profound theological differences that persisted well into the development of the institutional Church.

Marcionite or Pauline?

Marcion lived long enough to witness firsthand the Roman Church under the leadership of elders ordained by the Apostle Paul. He also observed what he perceived to be the gradual introduction of innovations and corruptions as leadership shifted to those aligned with the Apostle Peter. Disturbed by this transformation, Marcion became one of the earliest church reformers, calling for a return to the original, unadulterated form of Christianity rooted in the Pauline tradition.

While the Church Father Tertullian accused Marcion of founding a rival sect, his own writings inadvertently confirm the breadth and depth of the Marcionite movement. By the end of the second century, Marcionite Christians had established a vast and well-organized ecclesiastical network, complete with their own clergy and autonomous congregations across the Roman Empire. Tertullian, with evident frustration, remarked that “Marcion’s heretical tradition has filled the entire world.” He even went so far as to disparage the Apostle Paul himself, calling him “the Apostle of heretics”—a revealing admission of the threat Paul’s theology posed to the emerging Catholic orthodoxy.

Given this rapid growth and extensive reach, it is highly improbable that the Marcionite Church originated only after Marcion’s excommunication from the Roman congregation in 144 C.E. More plausibly, the movement had deep roots well before that date, and may at one point have surpassed the Catholic Church in size and influence. Historical evidence suggests that it continued to expand even after Marcion’s death.

The Catholic Church, in its effort to assert singular legitimacy, routinely labeled rival Christian communities by the names of their presumed founders—often designating them as heresiarchs. This rhetorical strategy served to portray all non-Catholic traditions as deviations from the “true” faith, while claiming direct continuity with Christ only for the Catholic Church. Yet, movements like the Marcionites did not view themselves as followers of a sectarian founder. They believed themselves to be the faithful remnant of the Church established by the Apostle Paul, and their theology reflected that conviction.

Thus, it is more likely that the traditional date assigned to the “founding” of the Marcionite Church is incorrect, rather than the implausible notion that it rose to prominence overnight. The more accurate conclusion is that the Marcionite Church was not a new invention, but rather the continuation of an authentically Pauline tradition that predated its formal excommunication from Rome.

In time, Paulinism became so influential that it could not be suppressed. Instead, it was absorbed, reshaped, and selectively redefined. Catholic authorities interpolated Pauline texts, attributed new writings to his name, and reframed his theology to harmonize with Petrine and Judaic traditions. The result was the syncretic construct of what is now known as Judeo-Christianity—an amalgam of the radical Gospel of Paul and the legalistic religion of the Hebrew Bible, giving rise to what would become the Catholic Church.

Whether Marcion’s teachings were entirely original or partially inherited from earlier apostolic sources—such as his teacher, the Apostle John—remains a matter of scholarly debate. It is worth noting that Marcion’s father, Philologus of Sinope, was himself one of the Seventy Disciples and a bishop ordained by the Apostle Andrew. Philologus was also known to be a follower of Paul in Rome, suggesting a family lineage deeply rooted in Pauline Christianity.

Regardless, the emergence of Marcion in the historical record marks the first documented appearance of a fully formed Pauline canon: the ten epistles of Paul and the singular Gospel of the Lord Jesus Christ. Marcion held that only Paul had received the true revelation of the Gospel and regarded all competing versions as corruptions. In this, he echoed Paul’s own words: “If any man preach any other gospel unto you than that ye have received, let him be accursed” (Galatians 1:9).

Did the Catholic Church subvert the teachings of Paul?

Yes, the Catholic Church—founded by followers of the Apostle Peter—and the Marcionite Church—established in the tradition of the Apostle Paul—were, from the beginning, rival expressions of Christianity. Though the Epistles of Paul are now included in the modern biblical canon, there was a time when the Petrine churches rejected both the letters and the apostleship of Paul altogether. As Pauline theology gained acceptance among Catholics, church authorities began producing edited copies of Paul’s letters, inserting interpolations designed to portray Paul as aligned with Catholic doctrine and subordinate to Peter’s leadership.

After Marcion’s death, Catholic authorities reportedly destroyed the original Pauline texts preserved by the Marcionite Church. In doing so, they ensured that only their redacted versions would survive, allowing them to retroactively claim apostolic authenticity for texts that had been altered to conform to Catholic theology.

The Acts of the Apostles was similarly crafted with the purpose of recasting Paul as a loyal Catholic missionary, harmonizing his mission with Petrine authority. Scholarly consensus holds that the same author who penned the Gospel of Luke also authored Acts—a narrative shaped more by ecclesiastical politics than historical fact. Indeed, many of the events described in Acts lack any corroborating historical record. As the scholar Hermann Detering observed: “The great majority of historical statements made in Acts about the life and person of the apostle Paul are legendary in character and thus are to be enjoyed only with great caution.” The figure presented in Acts is not the radical Apostle Paul of the original Gospel, but a domesticated “Catholic” version—one created to absorb Paul into a broader ecclesial unity.

Rather than continuing to oppose Paul, as was initially the case, the Catholic Church ultimately co-opted him—constructing a sanitized, orthodox version of the apostle and casting Marcion as a heretic for faithfully preserving Paul’s original gospel.

The accusation that Marcion “founded” his own church was a strategic invention of the early Catholic hierarchy. In truth, Marcion did not establish a new religion, but sought to preserve the authentic, Pauline Church rooted in the teachings of the Apostle to the Gentiles. To undermine this claim, Catholic tradition began depicting Paul and Peter as close allies—appearing together in church iconography, often as friends or even brothers in ministry.

This revisionist portrayal was designed to reinforce Catholic authority and gradually eclipse the widespread influence of the Marcionite Church. Through theological appropriation, institutional power, and historical suppression, the Catholic Church eventually gained the upper hand, but only by rewriting the legacy of Paul and marginalizing the church that had most faithfully preserved his message.

Are you heretics?

No, the Roman Catholic Church—as it exists today—did not yet exist at the time the Marcionite Christians established their own church. In fact, the Marcionite Church predates the formal organization of Catholicism by several generations. Many of the attacks against Marcion came later and were often written by critics with vested interests in discrediting his legacy. One of the most vocal among them was Tertullian. Yet even Jerome, a prominent figure in the early Catholic tradition, offered the following assessment:

“As to Tertullian, I have nothing else to say except that he was not a man of the Church.”

— Jerome, De Viris Illustribus

On this point, we are in full agreement with our Catholic counterparts.

Moreover, the most common accusations of heresy against the Marcionite Christians are either mistaken or entirely unfounded. Marcionites are not dualists. We are not docetists. We do not forbid marriage, impose celibacy, or prohibit the consumption of wine or meat. These doctrines more accurately describe the beliefs of Cerdo, a contemporary of Marcion, and his followers, the Cerdonians—an ascetic and gnostic group excommunicated by the Roman Church around 138 C.E.

Many of the charges originally brought against Cerdo were later falsely attributed to Marcion. Tertullian and other Catholic polemicists intentionally blurred the distinction between the two, depicting Cerdo as Marcion’s teacher rather than merely his contemporary. This conflation served to strengthen their arguments against Marcionite theology and to diminish its appeal among early Christians.

It is notable, however, that Cerdo and his sect also used the Testamentum or a form of it as their scriptural foundation. Like the Marcionites, they rejected the Hebrew Bible and did not view Jesus as the Jewish Messiah. This indicates that Marcion was not alone in his rejection of the Hebrew scriptures—multiple early Christian movements arrived at similar conclusions independently.

Under Bishops Hyginus and Pius I, the Roman Church excommunicated both Cerdo and Marcion—not for the scriptures they employed, but for their interpretations of those texts. It is highly plausible that the Testamentum itself, later associated exclusively with the Marcionite Church, was at one point in use among Roman Christians prior to 144 C.E.

At the conclusion of his excommunication trial, Marcion is said to have turned to the assembled bishops and presbyters of Rome and declared:

“I will divide your Church and cause within her a division, which will last forever.”

History suggests he was right.

Did Marcion try to become Bishop of Rome?

Yes, around the year 142 AD, following the death of Hyginus, the Church of Rome stood at a defining crossroads. Marcion of Sinope, bishop of Sinope and a devout disciple of both the Apostle Paul and John, sought to become bishop of Rome not as an innovator, but as a restorer—determined to return the Church to its authentic Pauline foundation. Even hostile Catholic testimony preserves the political edge of this moment: Epiphanius reports that after Hyginus’ death, Marcion was “lifted up by jealousy, since he did not receive the presidency.”

According to Marcionite tradition, the first legitimate bishop of Rome was Linus, ordained by Paul, and succeeded by Anacletus, the second Pauline bishop. The Catholic faction, however, traced its authority through Peter, and claimed Clement—the first Petrine bishop of Rome—as the founder of their episcopal succession. After Anacletus’s death, the Pauline line weakened, and the Petrine succession gained exclusive control, establishing a single episcopal line that would come to dominate the Roman Church. This shift set a precedent of two competing apostolic jurisdictions—Pauline and Petrine—vying for the soul of the Church.

To support his effort, Marcion donated 200,000 sesterces to the Roman Church. His gospel message was radical and clear: the God revealed by Jesus Christ was a God of perfect mercy and goodness, wholly distinct from the false god Yahweh of the Hebrew scriptures—a god of wrath, judgment, and legalism. Alongside him, Valentinus of Egypt also sought influence, promoting a mystical Gnostic worldview. Yet both men were ultimately rejected in favor of Pius (later Pius I), who upheld the Catholic project of merging Jewish scripture with Christian revelation.

Marcion initially remained within the Roman community, leading a growing reformist faction. But on the Ides of July, 144 AD, Bishop Pius excommunicated him, returned his donation, and expelled him from communion. According to Marcionite tradition, the following day Marcion stood before the Roman clergy and solemnly declared:

“I will divide your Church and cause within her a division, which will last forever.”

Two years earlier, in 142 AD, Marcion had already been ordained bishop of Antioch, succeeding Cornelius, a Petrine-aligned bishop. Upon assuming the post, he resigned his episcopacy in his native Sinope, where he had previously led a small but faithful Pauline community. From Antioch—a city that at the time rivaled Rome in power and prestige—Marcion began organizing a new ecclesiastical order, founded entirely on the gospel of Paul, the Apostolicon, and the Evangelicon. Anatolia, his homeland, quickly became the heartland of Marcionism, where his message of freedom from the law and rejection of Yahweh found a devoted and expanding audience. Many eastern bishops were in closer communion with Antioch than with Rome, aligning themselves with Marcion’s gospel of grace.

Like Rome, Antioch had a history of dual apostolic lineage. According to Marcionite understanding, its first Pauline bishop was Ignatius, a disciple of Paul who upheld the primacy of grace. In contrast, Catholic tradition traced its Petrine succession in Antioch back to Evodius, regarded as the first Petrine bishop of Antioch, allegedly ordained by Peter himself. This legacy of duality set the stage for the schism that followed.

In response to Marcion’s rising influence and consolidation of the Pauline faction, the Catholic Church swiftly installed Heron II as a parallel Petrine bishop in Antioch shortly after Marcion’s excommunication in 144 AD. Heron II represented the institutional wing of the Church, rooted in apostolic succession through Peter and theological allegiance to the Hebrew scriptures. Antioch became a divided episcopate, with Marcion and Heron II embodying two rival theological visions—one grounded in law and prophetic continuity, the other in grace and the radical freedom of Christ revealed apart from the law.

It was also in Antioch, around 169 AD, that the Catholic bishop Theophilus began to edit the Evangelicon, reworking Marcion’s gospel to align with the Catholic view of scripture and doctrine. This redacted and shortened version would later circulate as the Gospel of Luke, stripped of its original anti-Judaic and Pauline clarity. It marked the beginning of Rome’s efforts to co-opt and neutralize Marcion’s scriptural legacy.

Following his excommunication, Marcion formally established a separate Church, declared himself Archbishop—a title later twisted by his Catholic opponents who mocked him as the “Archheretic”—and ordained trusted disciples to key episcopal seats across the Christian world. Among the most significant were:

Apelles, ordained bishop of Alexandria, who would later succeed Marcion as Archbishop after his martyrdom.

Lucanus, ordained as the Marcionite bishop of Rome, continued the Pauline witness in the heart of Catholic power.

Onesimus, ordained bishop of Ephesus, a church founded by Paul and long faithful to its Pauline heritage. It was in Ephesus that Marcion had originally served as a disciple of the Apostle John.

Damas, ordained bishop of Magnesia on the Maeander, a city eager to embrace Marcion’s gospel over Rome’s legalism.

Polybius, ordained as bishop of Tralles, an Anatolian city that openly rejected Petrine ecclesiology.

Metrodorus, ordained bishop of Smyrna, where he led the Marcionite community in open and ongoing rivalry with the Petrine faction headed by Polycarp, one of Marcion’s most relentless adversaries. It was in Smyrna that Marcion had earlier delivered his famed Homily to Diognetus.

These churches—Alexandria, Rome, Ephesus, Magnesia, Tralles, Philadelphia, and Smyrna—stood at the forefront of Marcion’s ecclesiastical rebellion. Each declared its loyalty to the God revealed by Christ alone, rejected the authority of the Hebrew scriptures, and severed communion with the Roman and Petrine hierarchy. In these cities of Anatolia, the gospel of Paul took deep root, as Marcionite bishops took their place beside, or in place of, their Catholic counterparts.

In 154 AD, Marcion returned to Rome, not to debate, but to face martyrdom. He had been condemned by Roman authorities for fomenting division among the Christian communities of the capital. During this final journey, he encountered his lifelong adversary, Polycarp of Smyrna, who, upon seeing him, famously declared:

“Yea, I know thee as the first-born of Satan.”

Unmoved by scorn or condemnation, Marcion was led into the Colosseum, where he was martyred for the gospel he believed had been revealed through Paul alone—a gospel of grace, liberty, and the worship of the true God, wholly distinct from the false deity of the law.

Though the Catholic Church would enshrine figures like Pius and Polycarp as saints and defenders of orthodoxy, it was Marcion’s legacy that forced the early Church to define its canon, its creeds, and its institutional authority. The division he foretold became real—and in many ways, has never been healed.

Are there any notable Marcionite Christian martyrs?

Eusebius of Caesarea records that among the various early Christian sects, the Marcionite Christians produced the greatest number of martyrs. His testimony highlights the widespread devotion and steadfastness of the Marcionite faithful in the face of imperial persecution.

He names two martyrs in particular. The first is Metrodorus, Bishop of Smyrna, who was burned alive alongside Polycarp in 156 C.E., during the wave of Christian persecutions under Emperor Marcus Aurelius. Metrodorus is remembered for his unwavering commitment to the Gospel as preserved in the Testamentum.

The second is Asclepius, Bishop of Eleutheropolis, who suffered martyrdom during the Diocletianic Persecution. He was burned alive at Caesarea on January 10, 310 C.E., sharing the pyre with Peter Apselamus, another Christian martyr.

Eusebius also makes mention of an unnamed Marcionite woman—possibly a deaconess—who was executed in the arena of Caesarea around 257 C.E., during the reign of Emperor Valerian. Though her name is lost to history, her witness remains a testament to the courage and endurance of the early Marcionite Church.

Who were the disciples of Marcion?

Among the known disciples of Marcion of Sinope are Apelles of Alexandria, Lucanus (or Lucianus) of Rome, Syneros, Potitus, and Basilicus. Our primary source for these names is the early Christian writer Rhodo, who preserved some of the earliest accounts of the Marcionite tradition.

Apelles stands out as the most prominent and influential of Marcion’s disciples, often regarded as his theological successor. Apelles developed his own school of thought while maintaining fidelity to the foundational principles of Marcionite Christianity. He was also the first to advance a distinctly Marcionite theory of creation, attributing the creation of the physical world to an angel—an instance of deferred or indirect demiurgy that preserved the transcendence of God the Father while explaining the world’s mixture of order and disorder. From Alexandria, he engaged currents of philosophical exegesis and employed rigorous logical method, most famously in his Syllogisms, a work of argumentative “proofs” that marshaled contradictions and moral difficulties in the Hebrew Bible to argue that it could not be the pure revelation of God the Father as proclaimed by Jesus Christ and the Apostle Paul. These Syllogisms were not mere polemics but a structured program of critique that pressed opponents on consistency, causality, and divine character, aiming to clear space for the singular Gospel. Apelles’ Alexandrian associations also suggest contact with schools that prized textual criticism and philosophical theology, which helped shape his distinctive combination of biblical argument, moral reasoning, and spare Christ-centered proclamation. Later reports connect Apelles with a prophetic circle, associated with Philomena, but even there his emphasis remained on a simple rule of faith oriented to God the Father and Jesus Christ, and on a lean canon focused on the Gospel and Apostle. He also expanded the canon to include the Epistle to the Alexandrians and the Pastoral Epistles (1 and 2 Timothy and Titus). Moreover, Apelles advanced a theory of works-based salvation, stressing upright conduct and moral discipline as necessary for salvation. He likewise pushed back against the false accusations of docetism and crude dualism leveled against the Marcionites, affirming the real manifestation of Christ and clarifying that the world’s maker-angel was a subordinate power rather than a coequal rival to God the Father.

Syneros deserves special attention for articulating what appears to be the earliest Marcionite form of Trinitarianism. Described as teaching the “three natures,” Syneros outlined a triadic schema—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit—that, while not yet employing later technical language, nevertheless anticipates Trinitarian reflection. This early triadic pattern suggests that portions of the Marcionite movement were already thinking beyond strictly modalist or binitarian categories and experimenting with triadic confession in teaching, prayer, and possibly baptismal practice.

Lucanus appears to have assumed leadership of the Marcionite Christians in Rome following Marcion’s death. His teachings included the doctrine of the transmigration of souls, a form of reincarnation, and he upheld certain docetic beliefs, including the denial of the physical reality of Christ’s body and the immateriality and immortality of the soul. Lucanus’ school, however, seems to have faded by the end of the third century.

Potitus and Basilicus are notable for their apparent adherence to Binitarianism, the belief in two divine figures, which may also reflect the theology held by Marcion himself. In Marcionite contexts, Binitarianism typically meant confession of Father and Son as distinct divine realities, while treating the Holy Spirit not as a coequal person but as the operative power or gift proceeding from the Father through the Son. This differs both from modalism, which collapses Father and Son into a single person under different titles, and from later full Trinitarianism, which confesses three coequal, coeternal persons. Their contributions suggest that, while theological variations existed within the broader Marcionite movement, these differences did not result in formal schisms.

According to Rhodo, despite their differing views, the disciples of Marcion did not fragment into competing sects. They remained unified under the single identity of Marcionite Christians, a name consistently used by patristic sources. This theological tolerance within a unified ecclesial framework underscores the Marcionite emphasis not on strict dogmatic conformity but on spiritual conviction and adherence to the Testamentum, their distinct biblical canon. Unlike the Gnostic sects, which often fractured over doctrinal disputes, the Marcionite Church prioritized the purity of its scriptural foundation and the integrity of its religious spirit.

Who Were the First Marcionite bishops, presbyters, and deacons?

Marcion of Sinope, in his preserved epistles contained within the Synaxicon, names a wide circle of Marcionite deacons, presbyters, and bishops who accompanied or supported him during his captivity. Together, these figures reveal both the breadth of his influence across second-century Christian communities and the well-defined leadership structure already in place within the Marcionite Church.

Deacons:

Philo of Cilicia – Deacon of Tarsus, mentioned in the letters to the Smyrneans and Philadelphians; he travelled with Marcion toward Rome, highlighting Cilicia’s strong Marcionite presence.

Rhaius Agathopus – A Syrian deacon who joined Marcion at Troas and remained with him throughout the journey.

Burrhus of Ephesus – Deacon delegated by the Ephesian assembly; he met Marcion early on the route and carried messages on their behalf.

Crocus of Rome – Roman deacon who hosted and ministered to Marcion after his arrival in the capital.

Zotion of Magnesia – Deacon of the Magnesian church who assisted Bishop Damas in greeting the prisoner on his way to Smyrna.

Presbyters:

Apollonius of Magnesia – One of two presbyters sent by the Magnesian congregation to visit Marcion, offering encouragement and logistical aid.

Bassus of Magnesia – Fellow presbyter of the same church, partnering with Apollonius and Damas to ensure Marcion’s letters reached their destinations.

Bishops:

Damas of Magnesia – Encountered Marcion while Roman soldiers escorted the latter toward Smyrna; Marcion entrusted him with a letter addressed to the Magnesian flock.

Metrodorus of Smyrna – Bishop of Smyrna who received and hosted Marcion during his stop in the city, convened the local assembly, forwarded Marcion’s letters, safeguarded his personal effects, and acted as liaison with neighbouring churches. His steadfast leadership made Smyrna a rallying point for Marcionite believers, and he was burned alive in 156 C.E. during persecutions carried out under Emperor Marcus Aurelius, sealing his witness in martyrdom.

Polybius of Tralles – Described in the Epistle to the Trallians as a man of solemn bearing and gentle spirit, he travelled to Smyrna to stand in solidarity with Marcion during the final stages of the journey.

These bishops, presbyters, and deacons form a vivid portrait of committed Marcionite leadership—men who stood beside their founder in faith and service and whose cooperation attests to the vigor and organization of the Church he established.

Who are some other notable Marcionite Christians?

Among other notable Marcionite Christians preserved in the historical record are Prepon the Assyrian, Paul of Lebaba, Pitho, Megethius, and Marcus—each contributing in various ways to the development and spread of Marcionite Christianity.

Who was Apelles of Alexandria?

Apelles was the foremost disciple of Marcion. He began his ministry under Marcion’s guidance in Rome and later continued his theological work in Alexandria. Apelles remained active well into the reign of Emperor Commodus, which lasted from 180 to 193 C.E.

Did Apelles have any disciples?

Early Christian writers attest that Apelles had at least one prominent disciple, Severus. Epiphanius of Salamis (Panarion 45.1.3–4), Augustine (De Haeresibus 55), and Theodoret of Cyrrhus (Compendium of Heretical Fables 1.25) name Severus as the successor to Apelles and the leader of the Severian sect.

They also report that Severus and his followers repudiated the Hebrew Bible and its prophetic books: Epiphanius says they “revile the Law and the Prophets” (Panarion 45.1.4), and Augustine notes they “receive neither the Law nor the Prophets” (De Haeresibus 55). The record links Severus to Apelles and shows a decisive rejection of the Hebrew Bible’s authority, a stance that ties him back to Marcion.

In addition, the sources attest that Philomena the Prophetess was a disciple of Apelles. She originally served as a Marcionite deaconess and went to Rome ahead of Marcion to herald his arrival (Jerome, Epistle 133.4). Apelles confirmed her gifts, and her revelations were recorded in his now-lost Manifestations (Phanerōseis), which preserved her prophecies and visions.

According to Marcionite tradition, she was martyred in Rome, and her tomb is identified in the Catacombs of Priscilla, where her remains were discovered on May 24, 1802. Three tiles sealing the tomb read Pax tecum Filumena (“Peace be unto you, Philomena”), from which her name (Filumena, Greek φιλουμένη (philouménē), “beloved”) is rendered in English as Philomena. The two anchors, three arrows, the palm, and the ivy leaf on the tiles were interpreted as symbols of her martyrdom.

We maintain that, after miracles were associated with the tomb and remains, the Catholic Church attributed a constructed history unrelated to her true identity; later, on February 14, 1961, the Catholic Church ordered her name removed from all liturgical calendars, most likely when it was recognized that she was the Marcionite Philomena. Writers who mention Apelles’ prophetess include Tertullian (De Carne Christi 6; cf. Against Marcion 4.17), Hippolytus (Refutation of All Heresies 7.26), and the Latin Adversus Omnes Haereses 6; later notices occur in Epiphanius (Panarion 44–45) and Theodoret (Compendium 1.25).

Did Apelles have his own Gospel?

Writers within a century of Apelles do not name a separate “Gospel of Apelles.” When Tertullian addresses Apelles, he points back to his case against Marcion and “his own favourite gospel,” which is consistent with Apelles continuing to rely on the Evangelicon used in Marcionite circles.

Pseudo-Tertullian reports that Apelles “uses one only apostle” (that is, the Apostolicon) and drew on private readings he called “Manifestations” from the prophetess Philomena. These Manifestations were prophetic notes, not a narrative life of Jesus. The first explicit notice that names an Evangelium Apellis appears only with Jerome in the late fourth century, in his preface to Matthew, where he lists it among apocrypha. Later compilers echo him, but modern scholars treat the notice as a mistake, likely a muddled reference to the Manifestations or a cataloguer’s way of tagging the Evangelicon as used among Apelleans.

In short, Apelles did not compose a new gospel. He continued to preach from Marcion’s Evangelicon, and references to an “Apellean gospel” likely arise from confusion over Philomena’s Manifestations or over verses within the Evangelicon.

So Apelles taught the same as Marcion?

Yes. Apelles taught as Marcion did.

Apelles lived long enough to witness the first heresiological treatises and attacks that proliferated after Marcion’s death, and he directly repudiated the two accusations that became the standard calumnies against Marcionite Christians: docetism and dualism. We know this most clearly from his conversation with Rhodo, where Apelles does not “revise” Marcion so much as rebut hostile caricatures of him. And he likely did the same in his own major work, the Syllogisms—a kind of sequel to Marcion’s Antitheses, extending the same antithetical critique by systematic argument.

Only later, after Apelles’ death, did heresiologists increasingly feel compelled to frame him as a “heretic of Marcion.” This was not because Apelles had actually founded a new theology, but because their broader narrative required it: if Apelles remained plainly Marcionite while publicly refuting their stock accusations, then the web of polemical claims they had spun about Marcion would begin to unravel. Recasting Apelles as a deviant offshoot preserved their storyline.

The more straightforward historical reality is that Apelles is the first clearly “historic” Marcionite figure for whom we have sustained notice, and there are no reliable reports demonstrating that he materially departed from Marcion’s theology or from the Marcionite canon. Where later writers insist on differences, their reports are best read as retrospective damage control, not neutral description.

Who was Philologus of Sinope?

Philologus of Sinope, the father of Marcion of Sinope, is traditionally identified as one of the Seventy Disciples of Jesus Christ. According to early ecclesiastical tradition, he was consecrated as Bishop of Sinope by the Apostle Andrew.

Philologus is also believed to have been a companion of the Apostle Paul during his time in Rome. He is mentioned in the Epistle to the Alexandrians, where the text reads:

“Salute Philologus, and Julia, Nereus, and his sister, and Olympas, and all the saints which are with them.”

— Alexandrians 1:15

This passage attests to Philologus’s early role in the formation of the Pauline communities and his close association with apostolic leadership.

Did Philologus expel Marcion?

No, the origin of this rumor—repeated centuries later by both Tertullian and Epiphanius—that Marcion was expelled from the Church by his own father can be traced to a distortion of a local succession event within the Church of Sinope. Upon the death of Philologus, bishop of Sinope and father of Marcion, the episcopacy passed not to his son but to Phocas, a respected elder in the community. This decision was not the result of disfavor, but simply because Marcion was still in Ephesus at the time, continuing his spiritual formation and discipleship under the Apostle John. Only later, after Phocas was martyred in 102 C.E. during the persecution under Emperor Trajan, was Marcion chosen to succeed him as bishop.

This natural and orderly succession was later twisted by Catholic polemicists into a tale of scandal. Tertullian, writing in Adversus Marcionem, asserted:

“Marcion, the heretic, was disinherited by his own bishop-father, and cast out of the Church.”

— Adversus Marcionem 1.1

Epiphanius, writing more than two centuries later in the Panarion, embellished the accusation with a morally charged fabrication:

“When he was young, he seduced a virgin and was excommunicated by his own father, who was a bishop.”

— Panarion 42.1–3

These claims are entirely unsubstantiated by contemporary evidence and follow a familiar pattern of rhetorical slander employed by heresiologists to discredit theological opponents. According to Marcionite tradition, the truth is far different: Marcion was not a disgraced rebel, but a faithful heir to the Pauline mission, appointed after years of spiritual preparation and apostolic training. The narrative later crafted by Rome was not a record of history, but an act of institutional propaganda, designed to undermine Marcion’s legitimacy and obscure his apostolic inheritance.

Who were the Seventy Disciples?

The Seventy Disciples were early emissaries appointed and commissioned by Jesus Christ, as recorded in the Evangelicon. They were sent out in pairs on specific missions to prepare the way for His arrival in various cities and regions.

“And after these things the Lord appointed other seventy also, and sent them two and two before his face into every city and place, whither he himself was about to come.”

— Evangelicon 9:1

Below is the Marcionite Church’s compilation of the Seventy. Our method is twofold: it is scripturally grounded in the Evangelicon and the Apostolicon; and it cross-checks those names against traditional rosters transmitted through history, retaining customary honorifics and traditional locales where appropriate.

Also, unlike many inherited rosters, this list includes women named in Scripture and received in the tradition. It also notes that among the Seventy is Philologus of Sinope, recognized as the father of Marcion.

- Achaicus of Corinth

- Alexander of Ephesus

- Amplias of Odessos

- Andronicus of Pannonia

- Apelles of Heraclea

- Apollos of Alexandria

- Apphia of Colossae

- Aquila of Heraclea

- Archippus of Laodicea

- Aristarchus of Thessalonica

- Aristobulus of Britannia

- Artemas of Lystra

- Asyncritus of Hyrcania

- Barnabas of Milan

- Carpus of Berea

- Clement of Rome

- Cleopas of Jerusalem

- Crescens of Galatia

- Crispus of Corinth

- Demas of Thessalonica

- Epaenetus of Carthage

- Epaphras of Colosse

- Epaphroditus of Andriaca

- Erastus of Corinth

- Eubulus of Rome

- Fortunatus of Corinth

- Gaius of Ephesus

- Hermas of Philippopolis

- Hermes of Dalmatia

- Hermogenes of Asia

- Herodion of Patras

- James the Just

- Jason of Thessalonica

- Joseph of Arimathaea

- Junia of Rome

- Justus of Rome

- Linus of Rome

- Lucius of Cyrene

- Luke the Physician

- Marcus the Evangelist

- Narcissus of Athens

- Nereus of Rome

- Nicodemus of Jerusalem

- Nymphas of Laodicea

- Olympas the Martyr

- Onesimus of Ephesus

- Onesiphorus of Colophon

- Patrobas of Puteoli

- Phebe of Cenchrea

- Philemon of Gaza

- Philologus of Sinope

- Phlegon of Marathon

- Phygellus of Ephesus

- Priscilla of Rome

- Pudens the Senator

- Quartus of Berytus

- Rufus of Thebes

- Silvanus of Thessalonica

- Sosipater of Iconium

- Sosthenes of Corinth

- Stachys of Byzantium

- Stephanas of Achaia

- Tertius of Iconium

- Timotheus of Ephesus

- Titus of Crete

- Trophimus the Martyr

- Tychicus of Caesarea

- Urbane of Macedonia

- Zacchaeus of Caesarea

- Zenas the Lawyer

This list reflects the wide geographical spread of the early Church and the diversity of leaders commissioned by Christ to carry His message to the nations.

Who do you consider the Four Evangelists?

Marcionites do not use the phrase “the four evangelists” to mean four competing Gospel authors (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John). Our canon has one Gospel, and when the Apostle Paul speaks of “evangelists,” he is saying in the Pauline sense of authorized Gospel preachers and emissaries, not in later attributions of separate written gospels. This is precisely how the Marcionite spokesman Megethius argues in the Dialogues of Adamantius: when pressed on “four evangelists,” he rejects the category and insists that Paul’s language about “evangelists” refers instead to Paul’s own co-labourers, naming Silvanus and Timothy as the relevant referents.

Following that Pauline usage, the Marcionite tradition identifies the “four evangelists” as the four principal Pauline emissaries who carried, guarded, and proclaimed the Gospel alongside the Apostle in the churches: Silvanus, Timothy, Epaphroditus, and Tychicus. This is not a claim about four authored “Gospels,” but a claim about four evangelical ministers, the living messengers through whom the one Gospel was announced and the Pauline mission was sustained.

The later Paulicians, whom we treat as Neo-Marcionites in many respects, preserve this exact Pauline definition in the medieval record. Byzantine abjuration formulae explicitly accuse the Paulicians of “accepting” Paul’s disciples as types of the four evangelists, and in the same sequence they name the Pauline figures associated with that evangelic role, including Silvanus, Timothy, Epaphroditus, and Tychicus.

Who Replaced Judas Iscariot?

The Marcionite Church of Christ affirms that the Apostle Paul was personally appointed by the risen Jesus Christ and thereby elevated to apostolic authority, taking the place of Judas Iscariot as one of the true Twelve Apostles.

Who were the "false apostles" that Paul mentions?

The Apostle Paul employed the term “false apostles” primarily in reference to the Judaizers—a faction of Jewish Christians who insisted that adherence to the Mosaic Law, including circumcision, was necessary for salvation and for the acceptance of Gentile converts into the Christian faith.

Paul was unwavering in his opposition to the Judaizers, regarding their teachings as a fundamental distortion of the Gospel of Christ. He saw them not only as a threat to the universality of the Christian message but as disseminators of grave doctrinal error. Throughout his epistles—as preserved in the Testamentum—Paul offers a sustained and vigorous refutation of the Judaizing position, denouncing both their theology and their divisive influence within the early Church.

Paul’s commitment to the Gospel of grace led him even to publicly confront the Apostle Peter, whom he accused of compromising with the Judaizers. Paul rebuked Peter for showing outward support for their practices in certain contexts while privately distancing himself from their doctrines. This confrontation underscores Paul’s belief that the Gospel must be free from the legalism and ritualism of the Mosaic covenant.

All evidence within Paul’s writings suggests a complete rejection of any attempt to integrate Judaism into Christianity. His stance was later echoed by figures such as Barnabas, Basilides, Cerdo, and Marcion, as well as by various Gnostic Christians—all of whom opposed the inclusion of the Hebrew Bible within the Christian canon.

As Paul warned:

“For such are false apostles, deceitful workers, transforming themselves into the apostles of Christ.”

— 2 Corinthians 11:13

What other Christian groups descend from the Marcionites?

Some scholars, including historian Joseph Turmel, have noted striking theological parallels between the Marcionite Christians and the early Johannine community responsible for the Gospel of John and the Johannine Epistles. According to certain traditions, Marcion of Sinope began his ministry in Anatolia as a disciple of the Apostle John, suggesting a potential lineage of influence between these early Christian streams.

Numerous later Christian sects and movements appear to have inherited theological elements from the Marcionite tradition. Among these, the Paulicians stand out as the most prominent successors. Confined primarily to the territories of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire, the Paulicians first flourished in Armenia, where they encountered Zoroastrian and Manichaean doctrines. These interactions contributed to the development of their own syncretic theology.

Like the Marcionites, the Paulicians held the Apostle Paul in the highest regard, considering him the foremost interpreter of the Gospel. The founder of the Paulician sect, Constantine the Armenian, hailed from a Marcionite church in Mananalis, near Samosata. Around 657 C.E., he began to teach a new religious message based on the Marcionite canon. According to the account of Petrus Siculus—a Byzantine chronicler who lived among the Paulicians in Tibrike—Constantine received the Evangelicon and Apostolicon from a Marcionite deacon in Syria and distributed them among his followers, who initially preserved these texts as their authoritative scriptures.

Over time, the Paulicians appear to have expanded and modified Marcion’s Testamentum. They continued to use only the Gospel of Luke and retained most of Paul’s interpolated epistles, rejecting, however, the Epistles of Peter. Like the Marcionites, they entirely rejected the Hebrew Bible, rejected the resurrection of the body, embraced amillennialism, and also refused to venerate Mary.

Despite their shared Pauline foundation, the Paulicians diverged significantly from Marcionite theology. They embraced dualism, docetism, iconoclasm, and a non-Trinitarian understanding of God—positions that brought them closer to Gnostic traditions than to Marcionism proper.

Between 747 and 970 C.E., the Byzantine emperors deported large numbers of Paulicians to Thrace (in modern-day Bulgaria) as part of imperial resettlement and religious control efforts. These transplanted Paulician communities gradually evolved into a new movement: Bogomilism, which flourished throughout Bulgaria.

Bogomilism, in turn, gave rise to Catharism, a dualist Christian sect that spread through southern France between the 12th and 14th centuries. As political and religious pressures intensified in the region, many of the remaining Paulicians and Bogomils eventually converted to Roman Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy, or Islam during the period of Ottoman conquest. Ethnic groups such as the Banat Bulgarians and the Pomaks trace their ancestry to these historical communities.

Those Paulicians who remained in Armenia and were not deported gradually gave rise to the Tondrakian movement by the 10th century—a Christian sect that persisted in Armenia until as late as the 1820s.

If one accepts the theory of baptismal successionism—the belief that valid Christian faith communities can be traced through their rejection of infant baptism—then a theological lineage may be drawn from the Marcionites through the Paulicians, Bogomils, and Cathars, ultimately culminating in the emergence of modern Baptist traditions. Each of these historical movements consistently upheld the doctrine of credobaptism—baptism upon profession of personal faith.

Are you in Apostolic Succession?

Historically, the Marcionite Church was rooted in Apostolic succession.

Marcion of Sinope began his ministry as a disciple of the Apostle John in Anatolia. His father, Philologus of Sinope, was not only numbered among the Seventy Disciples of Jesus Christ but was also consecrated as Bishop of Sinope by the Apostle Andrew. Additionally, Philologus served as a companion and disciple of the Apostle Paul during his ministry in Rome.

Marcion succeeded his father as Bishop of Sinope, thereby inheriting a lineage of spiritual authority that could be traced to three apostles: Paul, John, and Andrew. On these grounds, the original Marcionite Church rightly claimed Apostolic succession.

Regrettably, that historical link has been interrupted due to centuries of suppression and the long discontinuity between the original Marcionite Church and its modern revival.

While the Marcionite Church does not regard Apostolic succession as a theological necessity for ordination or the administration of sacraments, we nonetheless hold it in high esteem. It is our hope that, in time, the Church may be restored to full Apostolic succession in continuity with its earliest foundations.

How long was Jesus' ministry?

The earthly ministry of Jesus Christ is understood to have lasted a little more than four years, reckoned from His descent and manifestation to the Passion.

The Evangelicon contains at least three distinct references to separate Passover observances, namely His first journey to Jerusalem, His second pilgrimage there, and finally the occasion of the Last Supper. Additionally, the Feast of Levi the Publican is widely interpreted as a fourth reference to a Passover meal, further substantiating the chronological framework.

By correlating these Passover markers with the foundational dates held in Marcionite reckoning, namely Christ’s descent into Capernaum on either December 31st, 28 C.E. or January 1st, 29 C.E., and His crucifixion on April 3rd, 33 C.E., we arrive at a ministry duration of four years, three months, and three days (from December 31st) or four years, three months, and two days (from January 1st).

For reference, the reconstructed Jerusalem Passover dates (Nisan 14, Passover eve and preparation, in the Julian calendar) for these years are as follows:

-

29 C.E.: April 18

-

30 C.E.: April 7

-

31 C.E.: March 27

-

32 C.E.: April 13

-

33 C.E.: April 3

Theological Questions

What are your Church Traditions?

Many church traditions later adopted by the Catholic Church and other Christian denominations can be traced back to Marcionite origins. These include the separation of the date of Christian Easter from the Jewish Passover, the rejection of Sabbath observance, the practice of Eucharistic fasting on Saturdays, open communion, the sign of the cross, the public reading of the Gospel and Pauline Epistles during worship, full triple immersion in baptism, and the use of a mixed chalice in the Eucharist.

It is also a long-held tradition among Marcionite Christians to eat broiled fish and honeycomb on Easter Sunday, in memory of the meal Christ shared after His resurrection.

In addition, many Marcionite liturgical practices were shaped by an antithetical theology—one that deliberately rejected the practices and beliefs associated with Judaism and the false covenant. This reflected the Marcionite commitment to the true covenant revealed through Jesus Christ, wholly distinct from the legalistic and carnal system of the Hebrew scriptures. For example, Marcionite Christians prayed facing west, in contrast to the Jewish practice of facing east. Likewise, the tradition of offering milk and honey to the newly baptized was a purposeful repudiation of Jewish ritual laws, such as the prohibition of honey in sacrificial offerings. These customs underscored the Marcionite belief in a radical break from the false covenant and full allegiance to the spiritual truth of the Gospel.

What was Marcion's Antitheses?

According to Marcion of Sinope, God the Father—who is revealed through Jesus Christ—had no prior interaction with the world before Christ’s manifestation. He was entirely unknown until that moment, transcendent and untainted by the material realm. In his now-lost work the Antitheses, Marcion presented a series of stark contrasts between the Hebrew Bible and the Gospel, between the god of the false covenant and the true God revealed in the Testamentum, between law and grace, judgment and mercy. He depicted Christianity not as a continuation of the Hebrew tradition but as a completely new and independent revelation, one that abrogated and superseded all that came before it.

In our chronology, we date the composition of the Antitheses to 139 C.E., aligning it with the Chronicle of Edessa’s notice (Seleucid year 449) that Marcion “forsook the Catholic Church.” That Edessan datum functions as the best external chronological peg for the moment when Marcion’s Gospel-versus-Law program is remembered as taking a written, public form.

Tertullian, one of Marcion’s fiercest critics, preserved a single quote from the Antitheses that illustrates Marcion’s approach:

“Whereas David in old time, in the capture of Sion, was offended by the blind who opposed his admission into the stronghold, so, on the contrary, Christ succored the blind man, to show by this act that He was not David’s son, and how different in disposition He was—kind to the blind, while David ordered them to be slain.”

Marcion’s critique was shaped by Hellenistic philosophical principles, especially Platonism, and he employed moral reasoning to contrast the inconsistency and cruelty of the Hebrew Bible deity with the compassion and righteousness of the God proclaimed by Christ. Marcion argued that the Testamentum and the Hebrew Bible are irreconcilable. Where Moses taught “an eye for an eye,” Jesus nullified this code of retaliation. Marcion highlighted Isaiah’s disturbing claim—“I make peace and create evil; I, the Lord, do all these things”—and contrasted it with Jesus’ statement, “A good tree cannot bring forth evil fruit.” Marcion emphasized the incompatibility between the fruits of the two trees: one bitter, one sweet.

He cited examples of moral divergence: in the Hebrew Bible, the prophet Elisha curses children, and bears maul them. Jesus, by contrast, says, “Let the little children come unto me.” Joshua halts the sun to prolong the massacre of his enemies, while Paul, quoting Christ, teaches, “Let not the sun go down upon your wrath.” The Hebrew Bible allows for divorce and polygamy; the Testamentum forbids both. Moses imposed strict Sabbath regulations and ceremonial law; Jesus deconstructs and transcends both.

Marcion also pointed to internal contradictions within the Hebrew Bible itself. The deity commands that no work be done on the Sabbath, yet instructs the Israelites to march around Jericho seven times on the Sabbath. Though he forbids graven images, he directs Moses to create a bronze serpent. Marcion questioned how an omniscient deity could ask, “Adam, where art thou?”—a clear sign, in Marcion’s view, of ignorance.

Even more strikingly, in Genesis, Jacob is said to have wrestled with the deity of the Hebrew Bible and prevailed—a blasphemous notion if applied to the true God. Likewise, before destroying Sodom and Gomorrah, the deity says, “I will go down now, and see whether they have done altogether according to the cry of it… and if not, I will know.” Marcion saw this as further proof that the god of the Hebrew Bible was neither omnipresent nor omniscient, but a limited, fallible being unworthy of worship.

Through these comparisons, Marcion advanced the case for a radical theological reformation: the rejection of the false covenant and its god, and the full embrace of the true covenant revealed by Jesus Christ through the Gospel and the writings of Paul.

What was Apelles' Syllogisms?

Apelles, a notable disciple of Marcion, authored a substantial multi-volume work entitled Syllogisms—comprising at least thirty-eight volumes—in which he offered a systematic critique of the Hebrew Bible and its depiction of God (Ambrose explicitly notes Apelles’ arguments “in the thirty-eighth tome” of that work). The title itself suggests that Apelles intended to build upon Marcion’s earlier work, the Antitheses, which had contrasted the false deity of the Hebrew Bible with the true God revealed in the Testamentum, emphasizing the irreconcilable differences between law and gospel, justice and mercy, wrath and grace.

Though the original text of Syllogisms has not survived, several fragments have been preserved through the polemics of later Catholic Church Fathers. Ambrose of Milan, in the fourth century, directed a number of rebuttals against Apelles in his treatise De Paradiso. It is through such responses that we possess rare direct quotations from Apelles’ lost work.

In one preserved fragment, Apelles addresses the inconsistency of divine foreknowledge in the Genesis account:

“Did God know that Adam would transgress His commandment, or knew He it not? If He knew it not, how then declareth He Himself to be Almighty? But if He knew, and yet gave commandment concerning that which He foresaw would not be obeyed, then did He speak in vain. But God doeth nought in vain, neither commandeth He that which is superfluous. Yet lo, He gave unto Adam, the first-formed man, a statute which He knew should not be observed. Wherefore, this writing proceedeth not from God, for the Most High doth nothing without purpose.”

Another excerpt questions the plausibility of the flood narrative and the Ark:

“By no means could it have been possible to bring aboard the Ark so great a multitude of beasts, and the provision for their sustenance for the space of a whole year, in so short a time. For if the unclean beasts are said to have entered two and two, that is, two males and two females of each kind, and the clean beasts seven and seven, that is, seven pairs, how then could the space, as it is written, have contained even four elephants alone? Verily, it is manifest that the tale is feigned. And if the tale be false, then surely this scripture proceedeth not from God.”

In a third passage, Apelles critiques the theological logic of the Eden narrative:

“How is it that the tree of life doth seem to confer more life than the very breath of God?”

On the supposed perfection of Adam:

“If God made man not perfect; yet if every man by his own diligence acquireth the perfection of virtue, doth it not appear that man obtaineth more unto himself than God bestowed upon him?”

On the knowledge of death:

“And if man had not tasted of death, surely he could not know that which he had not tasted.”

These fragments show Apelles continuing the Marcionite tradition of moral and philosophical opposition to the Hebrew Bible, exposing what he perceived to be contradictions, absurdities, and ethical failings in the text. Like Marcion, Apelles maintained that such scriptures could not have proceeded from the Father revealed by Christ, but rather from a lesser, false, and ignorant deity associated with the false covenant. His work represents a further refinement of the Marcionite conviction that Christianity stands in absolute distinction from Judaism—not as its fulfillment, but as its repudiation.

What is your connection to Hellenistic Philosophy?

Marcion and the early Marcionites engaged with Hellenistic philosophy to sharpen and defend their theological convictions, particularly drawing from Platonism, Stoicism, Cynicism, and to a lesser extent, Epicureanism—always holding revelation above reason. From Platonism, they embraced the idea that the highest reality is spiritual and that God is wholly Good—immutable, benevolent, and free from violence or contradiction. This philosophical insight helped articulate the radical moral and ontological distinction between the true God revealed by Christ and the morally deficient deity described in the Hebrew Bible. Stoic influence is reflected in Marcion’s personal asceticism and moral seriousness, though asceticism was not universally mandated among Marcionite believers. Cynicism, with its contempt for religious hypocrisy and institutional corruption, resonated with the Marcionite critique of both Jewish legalism and the authoritarian tendencies of the emerging proto-Catholic church. Even Epicureanism contributed to Marcionite thought by reinforcing the idea that a truly good God could not be the author of suffering, injustice, or fear—a perspective that sharpened their theological rejection of the false god as depicted in the Hebrew Bible. In all, Hellenistic philosophy provided the Marcionites with tools to express their faith in the supreme goodness of the Father and the uniqueness of the Gospel, without ever eclipsing the authority of divine revelation.

Do Marcionites read other Christian theologians?